Negli ultimi decenni si è affermata una tendenza ben precisa nella messa in scena operistica: la ricontestualizzazione radicale delle opere classiche. Non è più raro vedere La Bohème ambientata in un reparto di oncologia, o Semiramide trasportata su un’astronave. Queste scelte registiche, un tempo percepite come eccezioni audaci, sono ormai così frequenti da rappresentare una sorta di nuova normalità. Al punto che, se un regista decide di ambientare il Macbeth di Verdi in Scozia, viene etichettato come “tradizionalista”.

Mentre alcuni applaudono queste interpretazioni come innovative e rigeneranti, non posso fare a meno di pensare che spesso manchino il bersaglio.

Perché?

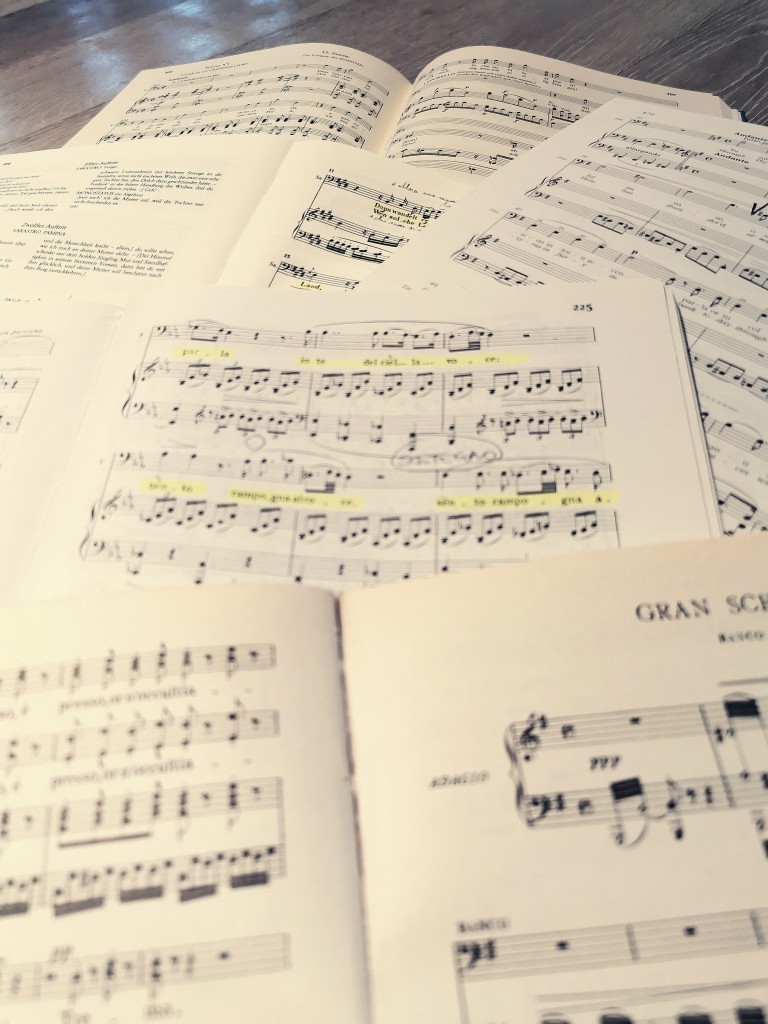

Perché esse tendono a trascurare la coerenza originaria tra musica e testo, imponendo una visione esterna su opere concepite con un equilibrio drammaturgico meticoloso. I compositori che veneriamo – Puccini, Rossini, Mozart – sapevano esattamente cosa stavano facendo. Il tempo, il luogo, il contesto di ogni scena non erano semplici sfondi, ma elementi narrativi e musicali indispensabili.

Quando si sradica un personaggio dal suo ambiente storico e culturale, si rischia di compromettere non solo l’impatto visivo e musicale, ma anche il ritmo interno e il significato profondo dell’opera.

Naturalmente, non tutte le opere reagiscono allo stesso modo a un cambiamento di ambientazione. Alcuni titoli sono, per loro natura, senza tempo e allegorici, e si prestano più facilmente a trasposizioni immaginifiche. Pensiamo al Flauto Magico o a Turandot: i loro mondi non sono legati a una realtà storica precisa, ma a dimensioni oniriche e simboliche. In quei casi, l’astrazione può servire la narrazione. Ma quando un libretto è profondamente radicato in un contesto sociale, culturale o politico specifico, ignorarlo indebolisce inevitabilmente l’efficacia dell’opera.

Non sarebbe molto più coraggioso scrivere e produrre nuove opere che parlino davvero alla nostra epoca, alla nostra estetica, ai nostri dilemmi? Se vogliamo raccontare una storia ambientata nello spazio o in un reparto oncologico, facciamolo con musica e libretto pensati per quel contesto. Questo sarebbe un vero abbraccio al presente, un passo audace verso il futuro dell’opera.

E se decidiamo — per esempio — di ambientare Traviata a New York, che ne è dell’atmosfera profondamente parigina di quest’opera, e dei riferimenti testuali alla Francia? Arriviamo davvero al punto di modificare le parole del libretto, o di adattare i sottotitoli, solo per far funzionare la regia? A quale prezzo?

Sì, lo so: mettere in scena un’opera di Verdi garantisce più biglietti venduti rispetto a una di uno sconosciuto compositore contemporaneo. Ma se scegliamo di proporre Puccini o Verdi, cerchiamo almeno di rispettare ciò che hanno scritto.

A mio avviso, abbiamo progressivamente attribuito ai registi d’opera il ruolo di creatori, quando in realtà dovrebbero essere – o almeno aspirare a essere – facilitatori, o meglio ancora sublimatori. Il loro è un lavoro profondamente creativo, sì, ma non senza limiti. È un atto di creazione all’interno di un perimetro stabilito dal compositore e dal librettista.

Un grande regista non ha bisogno di stravolgere un capolavoro per renderlo attuale. La sua arte consiste nel rivelarne l’essenza, non nell’oscurarla.

Come disse una volta Maria Callas:

«Quando vuoi trovare un gesto, quando vuoi sapere come recitare sul palco, tutto ciò che devi fare è ascoltare la musica. Il compositore ha già provveduto a questo.»

E credo che questo sia vero oggi più che mai.

Sono persuaso che il pubblico meriti di più.

Il pubblico entra in teatro per sognare, o almeno per emozionarsi, riflettere, stupirsi, lasciarsi incantare. Ma oggi, troppi spettatori escono delusi, o addirittura disorientati, e talvolta scoraggiati dal tornare.

Temo che questa non sia innovazione.

È una nebbia che avvolge il palcoscenico, offuscando ciò che un tempo brillava.

È ormai un cliché prevedibile che, se mai ha avuto un ruolo, lo ha già espletato da un pezzo.

Siamo chiamati a essere audaci, sì, ma non riscrivendo ciò che già ci parla. Piuttosto, creando ciò che ancora non è stato cantato.